QUALITY CYCLING CLOTHING SINCE 1996 - THE UK'S FIRST RETRO MANUFACTURER

QUALITY CYCLING CLOTHING SINCE 1996 - THE UK'S FIRST RETRO MANUFACTURER

RETRO APPAREL

COLLECTIONS

Cycling Clothing

ACCESSORIES

St Raphaël cycling team - Jacques Anquetil

May 20, 2019 5 min read

Jacques Anquetil, Raymond Poulidor and Federico Bahamontes at the Tour de France (1964). Photo Credit: Offside / L'Equipe.

Join travel writer and round-the-world cyclist Pedr Charlesworth as he explores the wacky world that was the legendary French rider, Jacques Anquetil, and his St Raphaël cycling team.

Raphaël Géminiani's new cycling team

In an age where Team Sky has instantaneously transformed into Team Ineos, it’s easy to forget that non-cycling related sponsors weren’t always commonplace in the sport.

Back in 1959, ex-pro rider Raphaël Géminiani was more than weary in deviating from the cycling sponsorship norm of the time. After struggling to finance his fledgeling cycling team through the standard channels, he eventually relented, striking a deal with the late-night aperitif producer – Saint Raphaël.

In a bid to escape the inevitable wrath of cycling’s governing bodies, Géminiani added a unique clause to the deal - if he was ever questioned by the cycling authorities, he could simply claim the team was named after himself. Unperturbed by the lack of nobility in self-proclaiming sainthood, Géminiani’s Saint Raphaël cycling team would go on to acquire a palmarès more than worthy of such a title.

Set up in 1959, the French team ran until 1964, with four Tour De France titles (1959, 1962-64), two Vuelta a España (1960, 1963) and one Giro d’Italia (1964) to its name. Despite being mainly focussed on the Grand Tours, the team notably picked up victories in the 1964 Tour of Flanders and 1963 edition of Gent-Wevelgem. The team’s roster included the likes of British riders Tom Simpson and Dave Rayner Fund president Brian Robinson, alongside Germany’s Rudi Altig. The majority of their victories, however, were won by the legendary Norman rouleur Jacques Anquetil.

Becoming Maître Jacques

Like many star bike riders to come, Anquetil was the son of a strawberry grower; brought up in a humble post-war world of hard graft and little pay. When his pedigree on two wheels became evident, cycling evolved into financial means to an end for the young Frenchman, who soon drew cheques from his domination of the amateur races. It was in these races where his talent against the clock soon came to light, eventually earning himself the title Monsieur Chrono and then Maître Jacques. True to his name, his real breakthrough into the public eye came from winning the Grand Prix des Nations in 1953 – at the time considered to be the unofficial time trial of the world. Here, aged just 19, the young Anquetil beat a field of the top professional riders by a mouth-watering 20 minutes.

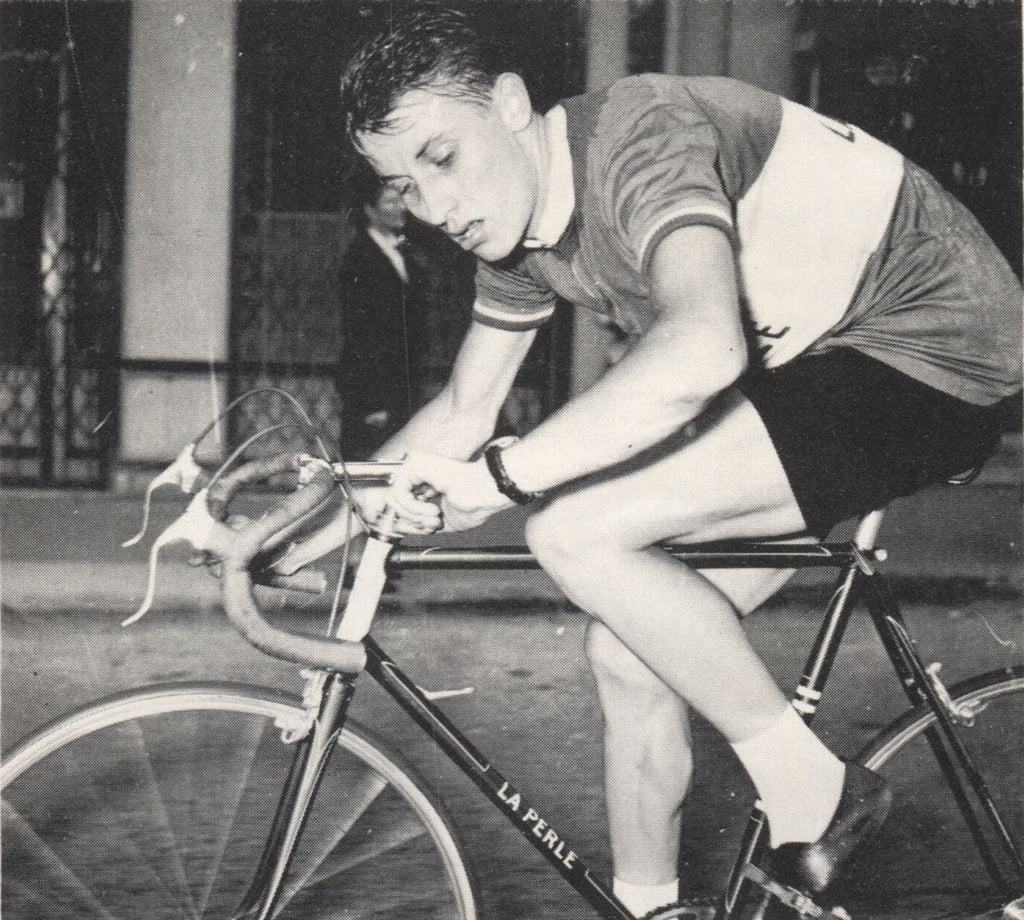

A young Jacques Anquetil checks his watch during the 1953 Grand Prix des Nations

His extraordinary early feats on the bike, combined with his lavish spending on extravagant cars, food and drink, soon captured the attention of the French public. Yet, despite being the pride of the nation, even the young prodigy wasn’t exempt from the law. Aged 20 he was enrolled in two years of military service in the army, where, after famously turning up to the barracks with 30 bottles of champagne, he still found time to break Fausto Coppi’s hour record on the track.

If his outlandish antics before major races stirred the public, his clinical way of racing often left them wanting more. Anquetil was an unbelievably strong rider, yet he was perceived to do the minimal work required to win – often holding out to claim victory in the time trial stages. Riding with a pedal stroke of pure aesthetic perfection, his fine finesse saw him efficiently win five Tour de France titles, two Giro d’Italia’s and one Vuelta a España. Still, there was one thing efficiency could not win – the hearts of the public.

It wasn’t long before Anquetil’s steely complexion of glacial blue eyes and light blonde hair became an emotionless symbol that mirrored his defensive riding style. A style that saw the rise in popularity of his assumed French rival, Raymond Poulidor. Consequently, Anquetil’s constant vanquishing of his popular adversary in the Grand Tours left Poulidor with the unenviable nickname - the Eternal Second. Although second place still seemingly resounded better with the smitten public, and despite his run of impressive results, Anquetil could do little to win them over. Not content with his run of play in the public eye, he decided to make a return to the much-loved races he’d previously written off as lotteries.

It was time to engage with the classics.

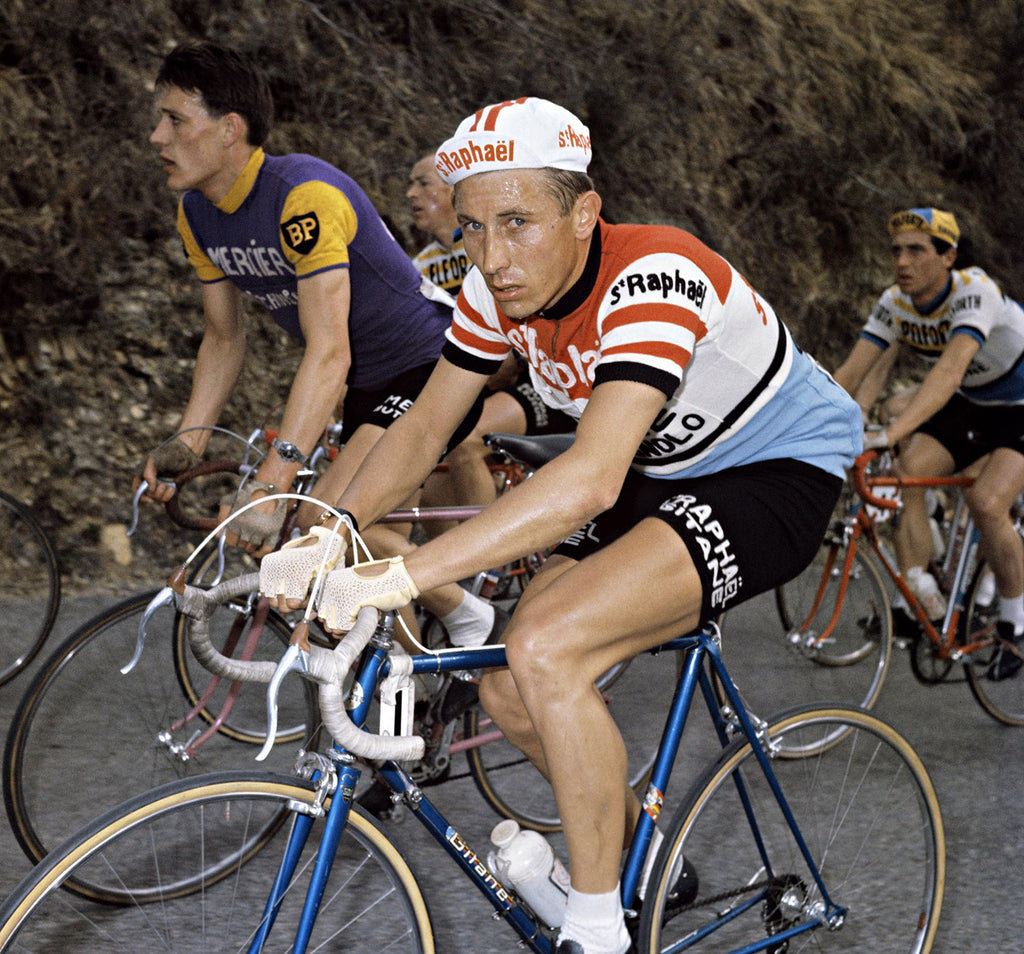

Jacques Anquetil at the 1964 Tour de France. Photo Credit: Offside / L'Equipe.

Jacques Anquetil and the Spring Classics

Never a fan of these fabled one-day races, Anquetil lined up at the start of the 1964 edition of Gent-Wevelgem in Raphaël colours, as an intrigued crowd watched on as the Frenchman showed his mettle. In a display that L’Equipe described as truly exceptional, Anquetil put in a monumental effort to resist the massed ranks of the best Belgian riders. Intent on preventing the Norman win in their own backyard, dozens of riders from various teams worked tirelessly on behalf of Rik Van Looy, Peter Post and Benoni Beheyt to reel him in. Yet, even this wasn’t enough to claw back the measly gap he had managed to open up. Somehow, he hung on for the final 3 kilometres before crossing the line in true Anquetil fashion, sitting up with a calm smile on his face that indicated no sign of the effort he’d just put in.

After that performance, Anquetil’s calibre as an all-around bike rider was unquestionable. With his place in the history books safely secured, he would look to engage in more extreme feats of racing in a futile attempt to recapture the public’s imagination. This would eventually lead to his famous winning of the 6th stage Dauphiné for the Ford cycling team, before flying straight to the start line (and winning) the 557km one-day Bordeaux-Paris race. Despite his incredible tally of victories on the biggest of stages, Anquetil’s confused personal life (he fathered a child with his step-daughter), combined with his public comments on doping meant he would remain only the favourite of the hardcore cycling fan. Those riding with him at the time understood his raw ability, and he was a popular character inside the peloton, even picking up compliments from his supposed rival Poulidor, who eventually conceded Anquetil’s superiority.

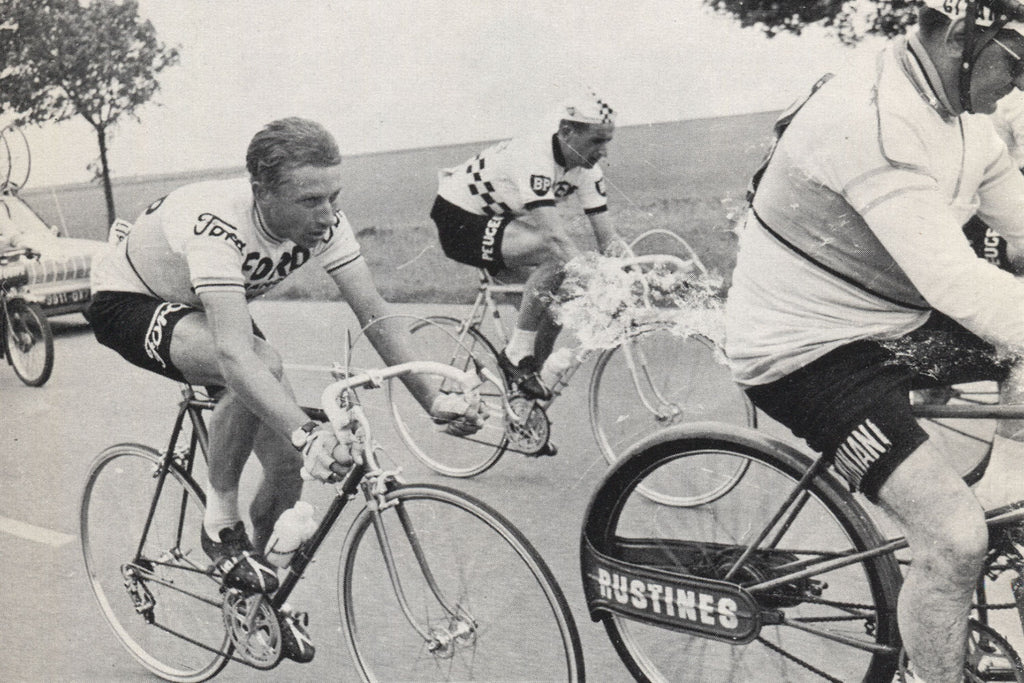

Jacques Anquetil's (Ford Hutchinson) greatest victory was the 1965 Bordeaux Paris, seen here with rival Tom Simpson (Peugeot BP).

There are very few to have matched Anquetil’s tally of Grand Tours (Merckx, Hinault and Indurain), so as Froome bids for his fifth Tour de France title this summer in Team Ineos colours, be sure to think of the Saint Raphaël rider with his five victories, staying up to 5am drinking champagne, beer and whisky, before heading out to victory the following day.

He may not be a role model worth emulating, but for his controversial character on and off the bike, Anquetil took the St Raphaël cycling team to new heights sat firmly on pillars of cycling folklore we shall probably never witness again.

You can buy the St Raphael retro cycling team jersey, cycling cap and matching phone case at Prendas Ciclismo.

Also in News and articles from Prendas Ciclismo

Prendas' Best-Selling Caps of 2024

January 21, 2025 4 min read

With 2024 in the books, we're looking back at your favourite caps of the year. From cult classic movies to the jungle with a whole lot of Italian flair, check out our best-sellers and grab a new cap!

Vas-y Barry! Hoban wins Ghent-Wevelgem for Gan Mercier Hutchinson

May 15, 2024 8 min read

In an extract from his autobiography, Vas-y Barry, the only British winner of Ghent-Wevelgem, Barry Hoban tells how he won the cobbled classic in 1974, beating Eddy Merckx and the cream of Belgian cycling.

Our Best Selling Caps of 2023

January 15, 2024 4 min read

We know caps here at Prendas Ciclismo, and we know that you love all the styles we have on offer. So every year, we look back at our best-selling cycling caps for the previous year for you to discover a few new styles. Is your favourite cycling cap featured on our list? Read on and see!

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …